Expanding Use of Cultural Properties with DNP’s Digital Archive Technology: Transforming Data from Means of Art Appreciation to Infrastructure

How can we best preserve and pass cultural properties to future generations? What technological solutions can address this challenge, which is faced by local governments and relevant institutions worldwide? We invited Keio University Associate Professor Yukihiro Fukushima, a leading researcher in the field of digital archiving, to engage in a dialogue with DNP employees who have developed various digital archiving solutions. They discussed the current situation and explored future possibilities of this evolving technology.

- A myriad of difficulties hindering digital archiving of cultural properties

- Frontiers in cultural appreciation: Technology enhances the enjoyment of cultural properties

- Future of digital archives: Is it possible to capture smell and sound?

- Potential of digital archiving: Preserving memories about areas being redeveloped

|

|---|

Yukihiro Fukusima

Associate Professor at the Faculty of Letters, Keio University

Fukusima attended Osaka City University (now Osaka Metropolitan University), where he completed doctoral coursework in Japanese history, but did not obtain a degree. After serving as a prefectural government employee at the Kyoto Prefectural Library and Archives (now the Kyoto Institute, Library and Archives) and the Kyoto Prefectural Library, he transitioned to academia. He held the position of Project Associate Professor at the University of Tokyo’s Graduate School of Interdisciplinary Information Studies before taking on his current role as Associate Professor of Library and Information Science. Fukusima is leading a movement to establish the field of digital archiving, leveraging the experience in the preservation and public display of historical materials he gained during his time with the Kyoto prefectural government.

|

|---|

Tomohiro Tajiri

Archives Business Development Department within the Cultural Business Unit of the Marketing Division at DNP

He is responsible for developing businesses related to the digital archiving of cultural properties and their utilization.

|

|---|

Kimitaka Hirasawa

Leader of the Archives Business Development Department within the Cultural Business Unit of the Marketing Division at DNP

He is responsible for developing solutions to promote digital archiving and its utilization.

A myriad of difficulties hindering digital archiving of cultural properties

— I believe that digitally archiving cultural properties involves not only a variety of stakeholders, but also artifacts that are challenging to archive or are in poor condition. This makes the task quite daunting. I’d like to ask Associate Professor Fukusima about the issues faced by those engaged in digital archiving.

Fukusima: The term "cultural properties" often brings to mind national treasures and important cultural properties. However, if we broaden this definition to include everyday artifacts, the scope of digital archiving expands significantly.

One of the main challenges we face is adapting the workflow for employees responsible for digital archives in municipal governments and related facilities. These employees are often assigned digital archiving tasks in addition to their regular duties, leading to, for example, a 30% increase in their workload. This places substantial strain on them. Over the past several decades, the challenge has been finding a way to integrate these additional tasks into employees’ existing responsibilities without further burdening them.

Another significant challenge involves evaluating work related to digital archives. Spmuecifically, foundational tasks for digital archiving, such as consistently acculating metadata (information about the content, properties, and usage of data) and establishing a system by selecting and consigning appropriate external partners, are often not adequately evaluated within organizations. While eye-catching outputs such as displays are undoubtedly important for raising awareness of cultural properties, I believe that the groundwork for these displays should also be acknowledged and assessed.

Similarly, the methods for evaluating digital archives as a business are not yet fully developed. I question whether the evaluation indicators should be limited to just the number of visits to digital content.

The revised Museum Act (the 2023 amendment designates digital archiving as one of the responsibilities of museums) has led to the current surge in digital archiving. To prevent this from becoming a temporary trend, it is essential to clarify and visualize the business value of these efforts.

— One of the primary goals of archiving is to preserve artifacts and materials for future generations. Therefore, is it a structural issue when the foundational work is often not adequately evaluated?

Tajiri: In most cases, we receive metadata from our clients when we provide support for digital archiving at municipal governments and facilities. Managing the metadata from the sorting process would likely require significant time and effort on our part. This underscores the challenges associated with foundational work, as Associate Professor Fukusima pointed out.

Frontiers in cultural appreciation: Technology enhances the enjoyment of cultural properties

— Despite the challenges faced by digital archives, DNP has been developing various products and solutions to showcase the appeal of cultural properties. Could you explain some of the key efforts?

Hirasawa: One of the leading initiatives is the “Artifact viewing tool series,” a collection of systems designed to help viewers appreciate cultural properties in an engaging way through digital data. It offers a unique appreciation experience with various systems, including a cube-shaped interface and connections to multiple devices, such as glasses and magnifying lenses.

For example, some systems allow viewers to rotate 3D models of the cultural properties displayed on the screen 360 degrees using a touchscreen and to examine details by enlarging the images to their preferred size. Additionally, using augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) technologies, some systems enable users to view digital representations of collected items that are not physically present, displaying them at life size.

This allows users to walk around the items and interact with them by using their hands.

-

*For details about the artifact viewing tool series, visit the site below:

https://www.dnp.co.jp/biz/theme/cultural_property/feature03/10161344_3688.html (in Japanese)

— This is very interesting. Experiences that go beyond the mere appreciation of physical cultural properties and that can only be offered through digital content can bridge the gap between users and cultural properties. Why is DNP, originally a publication printing company, involved in these ventures?

Tajiri: We engage in these businesses because we can leverage the photography and reproduction technologies that DNP developed from its printing processes. The skills and expertise we have cultivated in capturing subjects with high precision and faithfully reproducing them for purposes like catalogs align well with our clients’ needs for preserving precious cultural properties, forming the foundation of our digital archive business.

— So, there is indeed a connection with the original business. I believe that color reproduction is especially important in digitizing artworks. Do you face any challenges in accurately capturing the color tones of the original art pieces and reproducing them in a digital format?

Tajiri: Yes, we place great emphasis on color management during both photography and printing. Even The slightest differences in color between the digital data and the original can result in the true value of the artwork being lost. This is not a new concern; it’s standard practice in the printing industry. Thanks to our foundational technologies and expertise, we’re able to deliver high-quality digital content as we transition our media from paper to displays on monitors and smartphones.

Fukusima: Digital data produced through effective color management significantly change how they can be used in the future. If the data are of high quality, they can be applied across a variety of fields at a low cost. Most importantly, such data are likely to garner the trust of clients like temples, museums, and other institutions.

— Certainly, it is natural to assume that local governments and facilities that store cultural properties want to preserve them in pristine condition. I imagine you face a dilemma between what is technologically possible and what is not.

|

|---|

Hirasawa: In that regard, the project involving the Richelieu site of the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF) is still fresh in my memory. Their vases and other artworks made of silver or translucent materials that reflect or partially transmit light posed a challenge for us in terms of faithfully reproducing these pieces in digital form. However, we overcame this challenge by leveraging DNP’s photography and color management technologies, ultimately gaining approval from BnF curators, who were impressed with the precision of our reproductions from an academic standpoint.

Let me share an episode from this project. We had planned to hold an exhibition in Japan to showcase digital data and artworks, but the COVID-19 pandemic made it impossible to transport the artworks from France. As the person in charge of this project, I initially felt completely at a loss. However, by thinking creatively, I came up with the idea of displaying previously obtained high-precision digital data alongside the artifact viewing tool series of systems. Although we couldn’t exhibit any actual artworks, the event garnered significant media attention, allowing us to convey the message that “we are determined not to extinguish the light of culture” during difficult times. That experience remains a cherished memory for me.

— That's a touching episode, isn’t it? Are you involved in digital archiving of anything other than artworks, such as architectural structures like temples?

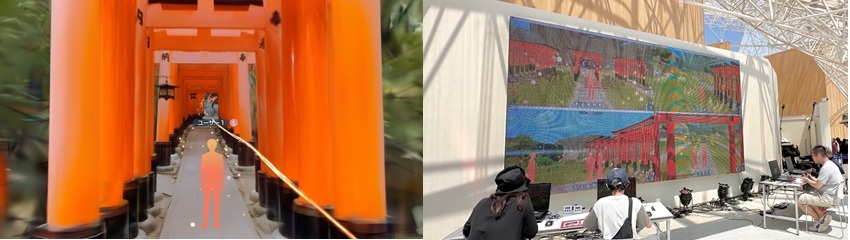

Tajiri: Recently, we created 3D digital data of a section of the Fushimi Inari Taisha precinct, which were used to develop a metaverse space where visitors can freely explore as avatars. This was unveiled at a limited-time event during the Expo, which was held in the city of Osaka. It represents an effort to archive a space both three-dimensionally and in a comprehensive manner.

|

|

Fukusima: Did you archive the shrine all the way up the mountain?

|

|

Tajiri: No (laugh). Given its vastness, we could only manage certain sections, including the Romon lower gate, the Honden main shrine, and Senbon Torii (the thousands of vermilion torii gates). It previously required a vast amount of time and resources to obtain digital data for a space, but thanks to the emergence of new 3D technologies, such as Gaussian Splatting, which can generate 3D data from multiple photographs, we have been able to streamline our work.

— I’m interested in the behind-the-scenes processes involved in photographing sites. I believe it is essential to capture objects in three dimensions when photographing. Do you use drones for this purpose?

Hirasawa: Yes, we do use drones for photography. However, there are many hurdles to consider, including weather conditions, sunlight, and the permit applications required for flying drones. The challenges are not limited to drone usage; strict conditions are often imposed on photographing cultural properties, such as regulations regarding lighting and the time allowed for photography. This is why scouting locations before taking photographs is essential. Indeed, there are many factors we can’t fully understand until we actually visit the photography locations.

Tajiri: Above all, collaboration with curators, who have the deepest understanding of the value of cultural properties, is essential. Fully grasping the story we want to convey, how to convey it, and to whom — while also sharing this narrative with all team members — will significantly enhance the quality of our output. We are technological professionals, but we are dedicated to thoroughly learning about the attractions and fundamental values of artworks from curators and working together to produce compelling content.

Future of digital archives: Is it possible to capture smell and sound?

— Technological advancements have expanded the methods available for digital archiving. However, are there still pressing issues that need to be addressed?

Fukusima: One key issue is licensing. Even if we have digitized data, it is of little value if we can’t use it due to rights restrictions. Additionally, cultural properties and materials are often overlooked unless they are digitally archived and accessible. For instance, it has long been noted that researchers from abroad are often hesitant to conduct research on Japan. In contrast, countries like China and South Korea are actively resolving rights issues to create a more conducive environment for research. I believe that digitally archiving cultural properties and clarifying the ownership of their rights are fundamental prerequisites for their effective use.

— By addressing these issues, will the scope of digital archiving continue to expand in the future?

Fukusima: I believe it will. For instance, if we can archive not only visual assets but also food, music, and even smells, the range of experiences will be significantly broadened. So far, initiatives have mostly been limited to experimental efforts, but the wealth of accumulated content and today’s technological capabilities should enable us to adopt more practical approaches.

— It is thrilling to consider the possibility of archiving smells and sounds. Do you envision exploring such new frontiers?

|

|

Hirasawa: Absolutely — we are excited to take on this challenge. In fact, technology has emerged to quantify smells and tastes alongside research aimed at capturing data on craftsmen’s movements for reproduction. I believe that generating innovative ideas about how future digital archiving can evolve, without being constrained by preconceptions, will pave the way for new value creation.

Potential of digital archiving: Preserving memories about areas being redeveloped

— I’d like to further explore new digital archiving methods. Are there any insights we can gain from the examples of France’s BnF and Fushimi Inari Taisha?

Fukusima: Mr. Tajiri pointed out that architectural structures can be digitally archived in three dimensions and comprehensively, citing Fushimi Inari Taisha as an example. This technology can be effectively utilized to preserve the memories of communities that are being lost due to redevelopment.

Community scenery is often renewed as development addresses various needs. However, we must not forget to record the history and the lives that once existed in these locations.

For example, the area designated for the third runway of Narita Airport (scheduled for completion in March 2029) was once the site of an old hamlet. Before construction began, researchers visited the hamlet to digitally archive it at their own expense. Additionally, a team from Shibaura Institute of Technology is photographing Tokyo’s Tateishi area (in Katsushika-ku), which is currently undergoing redevelopment, using both ground-level and aerial drone photography.

I’m interested in finding out whether DNP’s technology can be utilized for such endeavors. A replica of the stone walls of Edo Castle is displayed at Ichigaya Station (on Tokyo Metro’s Nanboku Line, near DNP’s head office). If we digitally archive the replica, the number of exhibited items could increase, and the content could become more in-depth, allowing more people to engage with it. This could open up new business opportunities. As this example shows, recording community memories for the future is valuable not only for researchers, but also for residents and developers.

— In this way, we can experience community memories later without being physically present.

Fukusima: That’s correct. A comprehensive archive that captures various aspects of a community can aid in preparations for reconstructing areas in the event of a disaster. For instance, municipalities like Taiji Town in Wakayama Prefecture, which has decided to relocate much of the town to higher ground as a precaution against tsunamis, will see their entire old town center disappear. Erasing the memory of the town center would be a significant loss. DNP’s technologies should be capable of preserving the history of such a disappearing community semi-permanently.

— We should preserve not only individual cultural properties but also the memories of entire towns or regions. This approach will greatly expand the role of digital archives, won’t it?

Tajiri: We strongly believe that there are possibilities of using digital archiving in this way. The revisions made to the Museum Act (effective from April 2023) have paved the way for using archives not only for preservation, but also for various other purposes.

For example, if digital archives are used in school education, they can help children strengthen their connection to their hometown. In fact, some schools are utilizing the “2D viewing system in cubic interface,” a product from the artifact viewing tool series, for educational purposes.

|

|

One of the strengths of the 2D viewing system is its design, which enables users to intuitively search for stored artifacts that interest them. This design encourages children to appreciate the shape, pattern, color, and beauty of the artifacts, motivating them to explore the actual items in museums.

— By “experiencing” cultural properties, we may bridge the gap between us and them.

Tajiri: That's correct. As Associate Professor Fukusima mentioned, initiatives to preserve a community’s memory will foster civic pride (a sense of pride in and attachment to the community) among residents. Furthermore, if digital archives reach beyond the local population, they could also motivate tourists to visit.

We envision a future where digital archives function as a “regional infrastructure” that supports education, tourism, and enhanced town development. Our goal is to redefine their value from being merely tools for art appreciation to becoming resources that everyone can engage with in their own initiatives.

Fukusima: That’s a very interesting perspective. I believe that the technology and knowledge related to digital archives can be applied to a much broader range of fields. The question of how to preserve and utilize a diverse range of cultural properties should not be addressed solely by specialists. In this context, I see the term “regional infrastructure” as a promising step toward evolving digital archives into an entity that as many people as possible can engage with.

|

|

- *Please note that the information provided is current as of the publication date.

January 29, 2026 by DNP Features Editorial Department